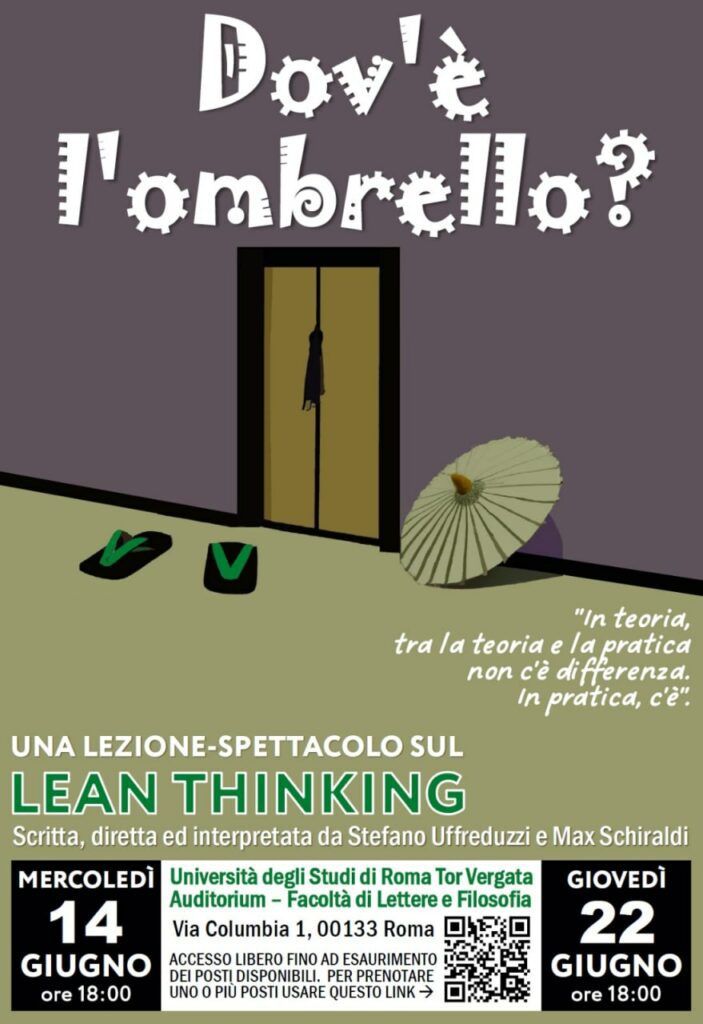

On June 14 in Rome, a lecture-show on Lean Thinking will be held at the University of Tor Vergata. To sign up go to this link.

I wanted, before signing up, to do a quick review by contextualizing the topic.

The beginnings

With the Second Industrial Revolution and after the end of World War II, new production models and methods were developed. This happened both as a response to the economic conditions in which they matured and because of the insights and cultures of the men who devised them.

Henry Ford and the assembly line

Automobile production began in Europe where, for example, Opel began construction in 1899. Cars were manufactured in small workshops, using artisanal methods and in small quantities. So the costs were high and their market was the nobility and the wealthy bourgeoisie.

Henry Ford in the United States wanted to produce a car that was economical, easy to use and durable. He had a fixed idea of“putting the world on wheels.” So in 1908 he began producing the Model T car, which, indeed, for those times, was quick to assemble, easy to operate, and simple to maneuver on all surfaces. His innovative skills led him to perfect its production process to be able to produce more cars. In 1913 he introduced the assembly line in his factory based on conveyor belts. The basic concept was to bring the work to the workers rather than having the worker move around the vehicle. It was a success given that by the time Model T production ceased, more than 20 million had been sold.

The production model adopted by Ford can be identified as a PUSH type which, due to demand, was to push as many cars into the market as possible.

Toyota and the challenge of continuous improvement

A little later than in the U.S., an automobile company Toyota was also born in Japan. It is a company whose founding father is

Sakichi Toyoda

, a character with an inventor’s soul. Sakichi patents a series of innovative frames that optimize human labor that are produced by his company theToyoda Automatic Loom Works, Ltd. In 1933, his son

Kiichirō Toyoda

took his father’s place and opened the automobile manufacturing division.

But World War II begins and the Japanese government pushes for the company to specialize in truck production for the Imperial Army. Kiichirō then spins off the automotive division and establishes Toyota Motor Co., Ltd.

Another man of ingenuity was

Taiichi Ohno

, who started out as a technician and began working in the textile industry closely with operational work where he already began to work out a number of organizational improvements. Having moved into the auto industry Taiichi had no powers and could not make decisions that were the responsibility of other managers. Driven also by patriotic spirit, he began to make his workers work in teams and made them focus on improving operational processes consistently.

At the end of the war Ohno has in mind Toyota’s main problem: as long as they produced vehicles for the military they could imitate American and European mass production, that is, produce the exact same vehicles en masse. But in the postwar period, Japan’s domestic market was not large enough to absorb a production PUSH of mass production, there was a lack of capital, and the high costs of production, particularly of raw materials, did not allow for the creation, as was the case in the West, of economies of scale that would lead to lower unit costs.

Ohno was clear that a different vehicle had to be manufactured for each market demand, driven by the specificity of demand. It is what is called the PULL model, but to achieve this new mode required radical process improvement, dramatically reducing waste, consequently reducing tooling and semi-processed waiting times. A set of procedures capable of ensuring perfect synchronicity of production operations in a continuous flow had to be created.

He made several trips to the U.S. to study the Fordist model, but was negatively amazed. Particularly from how the Ford Motor Company had organized the assembly line, in his view full of “MUDA” (waste). Instead, he was particularly impressed by the model of a chain of stores, the Piggly Wiggy, which featured a particular way of setting up an obligatory route along which products placed on shelves could be picked up and then paid for on the way out. Back in Japan he thought of transposing this principle to Toyota, thus adjusting the rate of production according to demand trends, a principle opposed to Fordism, which was characterized by mass production focused on stimulating supply.

The 1950s began a long journey that led Ohno to the position of General Manager of Toyota. It is the path that gives birth, from the fruitfulness of corporate culture, to the famous

Toyota Production System (TPS)

based on Jidoka and Just-in-Time.

Jidoka is a term created by Toyota that is pronounced exactly like the Japanese word automation (Jidōka), but it is spelled differently. As the character meaning “human being” has been added to the standard spelling, its meaning has changed: it means automation with human intelligence. That is, to equip machines with a system that autonomously prevents unforeseen events in their operation. Design machines used in production so that they intervene at the very moment defects are produced to a product, stopping and reporting them.

Just-in-Time was coined by Kiichiro Toyoda. This system requires that each component be delivered to the assembly line exactly when it is required and only in the quantity needed. This eliminates space used as storage and reduces the accumulation of unused material awaiting processing.

The Lean Thinking

In 1996, James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones, published the book entitled Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation. They not only describe the birth, principles, and advantages of the Toyota production model, but also hypothesize its application in all areas of business.

The difference between TPS and Lean Thinking.

Lean Think ing and the Toyota Production System (TPS) are two closely related concepts, as Lean Thinking is based on the TPS developed by Toyota in the 1950s and 1960s.

The

TPS

is an integrated production system that aims to reduce waste and eliminate activities that do not add value to the final product. TPS includes several concepts and tools, such as Just-in-Time, Jidoka (self-control) and Kaizen (continuous improvement), which are used to improve efficiency, quality and productivity.

Lean Thinking is a business management philosophy that focuses on eliminating waste and creating value for the customer. It is based on the same principles as TPS, but goes beyond production and applies to all aspects of the organization, including administrative and service processes. Promotes throughout the company a culture of continuous improvement and staff involvement, focusing on customer needs and process optimization to provide added value.

What lies ahead

I have not expanded on Lean thinking because I invite you to attend the event-show in June where it will be discussed in detail and in an entertaining way.

The reflection I make instead is that I do not know how relevant these models still are for production systems and that the whole production model should be rethought. Perhaps this is immature and, I hope, inaccurate thinking, but it is based on what I am seeing in recent times.

While these production models see the individual company at their center, the business world, driven by the benefits of globalization, has centralized much of production in one place. The place, of course, is China, which is the same state that has secured most of the supplies of raw materials critical to the production of the technology. This is beginning to show negative effects.

Example. Passing by a Lexus dealer (coincidentally the luxury brand owned by Toyota) out of curiosity I asked about the Lexus UX. At the end of the ritual illustration the conversation was this:

“But what is the delivery time?”

“For the Urban version (the basic one) 10 months.”

“What about the others?”

“It depends on 16 to 18 months.”

“How come so much difference?”

“Because there are few components and they only produce basic versions.”

Again out of curiosity, I also asked about the top model, the new RX. Price aside, the answer on delivery time was peremptory: “There is no possibility of making any forecasts on timing.”

Another example? Try ordering 1-2 new enterprise-grade network equipment, not hundreds. The lead time is 12 months.

I think the COVID period, which saw the closure of many trade routes from China to the West, was the event

Black Swan

that worried many Western companies. The reaction was probably to “stockpile” more than necessary in defiance of just-in-time.

This also observes from the movement of full and empty containers between China and the West. From the little data found on the internet it seems as if, after a recovery at the end of COVID, more empty containers than usual are being stationed in the West. Let’s say it is something that would be worth doing an in-depth study on.

Let me explain further. Think of the total number of containers in the world, all occupying a certain space that is distributed among the various ports in all states. When they move, they travel between production points and consumption destinations, full from producer to consumer and empty from consumer to producer. But if the consumer does not order other things it is better to pay for the stationing of the empty container instead of having it returned. Empty ones are turned back when exchanged for full ones. Now if we have more empty containers in Western ports, the cases are two: either we are expecting a collapse in demand, or China is centering its supply to us. And neither of the other two appeals to me.

Sakichi Toyoda Founds Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, Ltd.

1926

Taiichi Ohno

began working at Toyoda and immediately began trying to improve his team's work

Kiichirō Toyoda

, who took over from his father Sakichi Toyoda, opens the division to produce automobiles

World War II

1939-1945